04

Take a Picture and Move On

A conversation between iconic Interior Designer Ben Kelly and Ross Hunter, owner of design practice Graven Images.

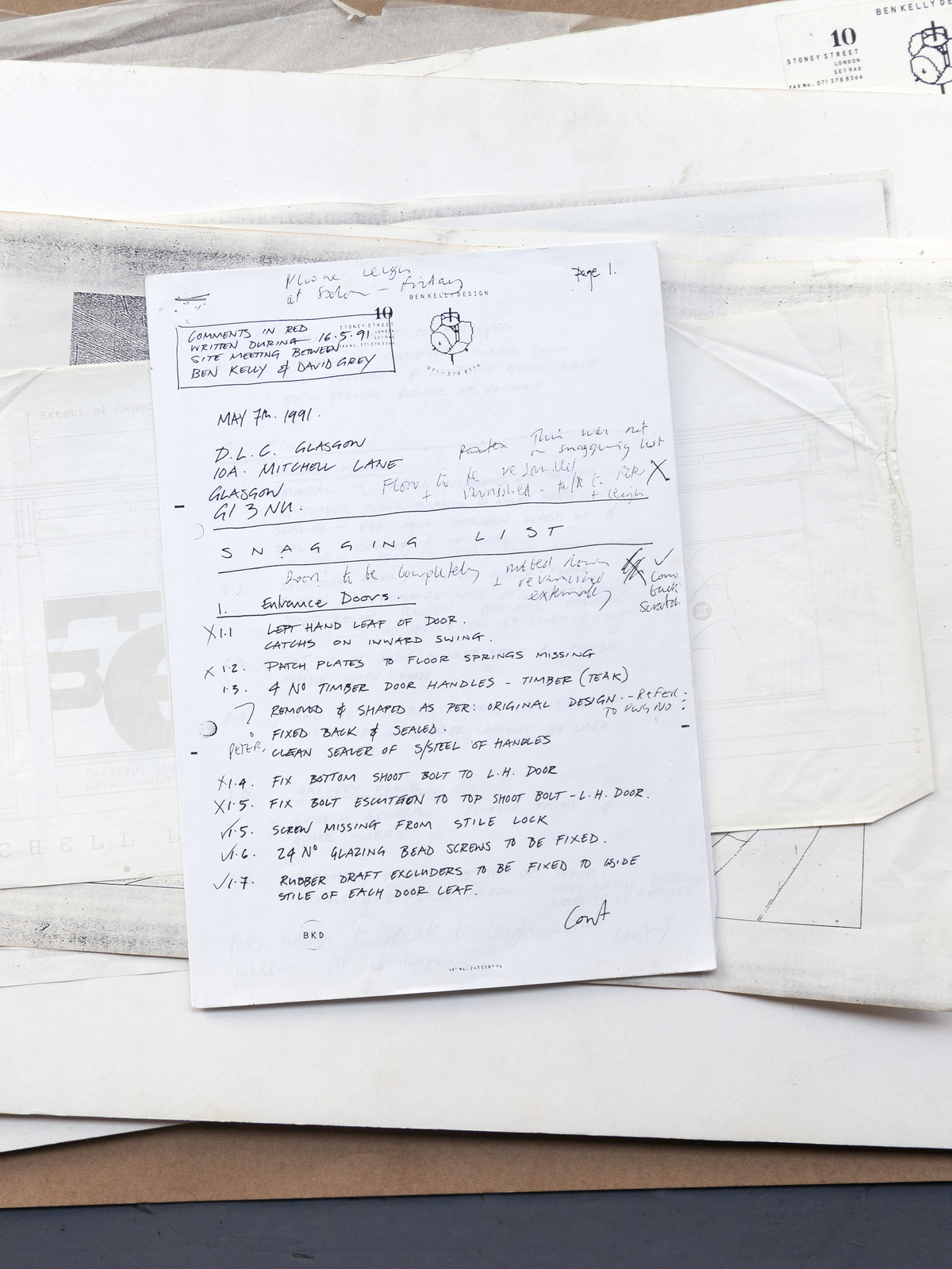

Original drawings and notes by Peter Mance.

In memory of Derek.

Sometimes a place changes a city, a kind of catalyst for transformation and evolution. The combination of Bar Ten/DLC in Glasgow was such a place. We asked Ross Hunter to chat with Ben Kelly about this, and other things.

Ross

This seems to be a good time to talk about Bar Ten, and in particular to talk about your work. This morning, just because I hadn’t been past for a little while, I walked over to Mitchell Lane and I stood in front of the former Bar Ten and had a moment.

Ben

How unpleasant was that?

Ross

It’s awful really – I’ll send you a picture afterwards – but really everything that is bad that’s happened in interior design over the last 10 years seems to be captured there. Not nice!

Ben

It’s a bit like what’s happening with rest of the world.

>

Yeh I know, it’s funny (it might seem a little trite) but it’s almost a bit like the Art School as well. I know that there’s a different scale of disaster perhaps, but you know how certain spaces just become personal. And it felt like there was something really personal had happened with Bar Ten too.

The Sex Pistols rehearsal room on Denmark St. London, as graffiti'd by John Lydon.

That’s very nice of you to say – and other people have said the same thing to me. It’s one of my favourite projects that we ever did really and I was also incredibly flattered when all that time ago there was an attempt to get it Listed. That was a major accolade as far as I’m concerned.

I found some stuff online about that. I was quite surprised to see that it was in 2002. Andy Harrold was the cheer leader for that (Andy’s an old mate of ours). It just took me back, it was interesting, and actually I think it was a great idea. I subsequently saw in some of the online stuff that there was a similar suggestion that The Haçienda should have been protected or Listed as well. I don’t know how you feel about it but is Listing the best way to protect these kind of spaces?

I don’t know, I really don’t know. It’s kind of weird how things happen. Just going back even further in time – I couldn’t even tell you what year it was – but sometime towards the end of the seventies, Malcolm McLaren approached me to design (and I use that word loosely) the Sex Pistols rehearsal rooms on Denmark Street, London’s ‘Tin Pan Alley’. Which I did, or at least I made them habitable for them to do their worst with (or their best, whichever way you look at it). John Lydon eventually came along and kind of put graffiti and drawings on the walls – which was basically, I think MDF – although had MDF been invented? Anyway he did, and then the years rolled on, and they became offices effectively. The fashion label Agnes B had offices in there for a while.

That’s a bit of a shift!

Then a big chunk of Denmark street was sold, and that little building went with the sale.

An architect was commissioned to do work to the development and the lining of the walls in that particular room had been covered in plaster board or something, and they pulled the plaster board away to reveal all of this graffiti.

A sort of Tutankhamun moment!

Well indeed, and English Heritage got involved and that room has subsequently been listed!

That’s fantastic!

I would say primarily because John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten) did his worst or his best, and I think that’s given it some kind of credence or whatever you call it for that Listing. But that’s an extraordinary thing I find.

Going back to Bar Ten and Listing, that would have been amazing, because I think it’s not often that places like that become what Bar Ten did become. It seemed to have become the kind of gathering place for the creative community of Scotland.

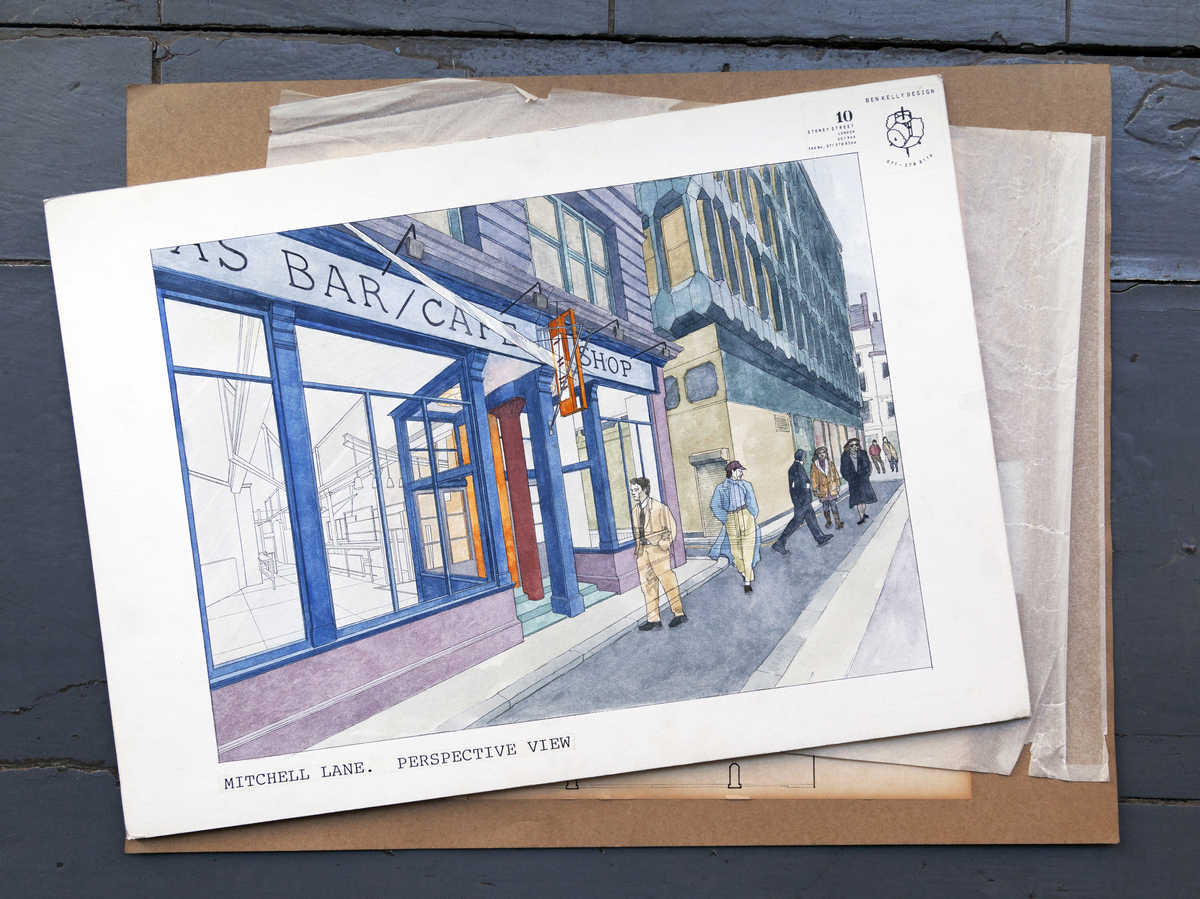

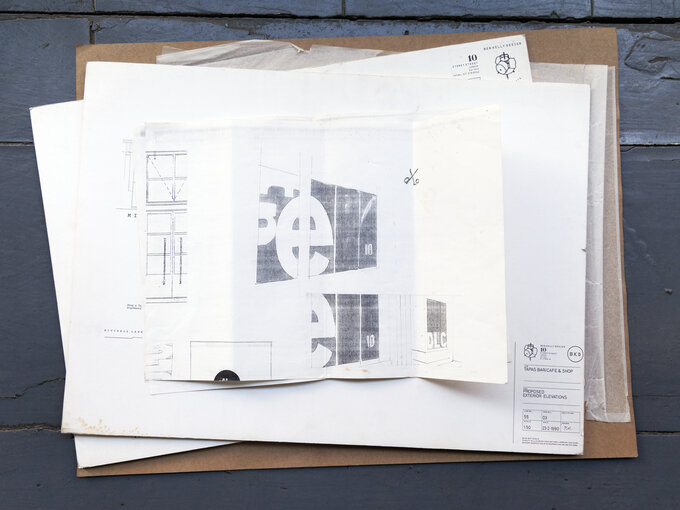

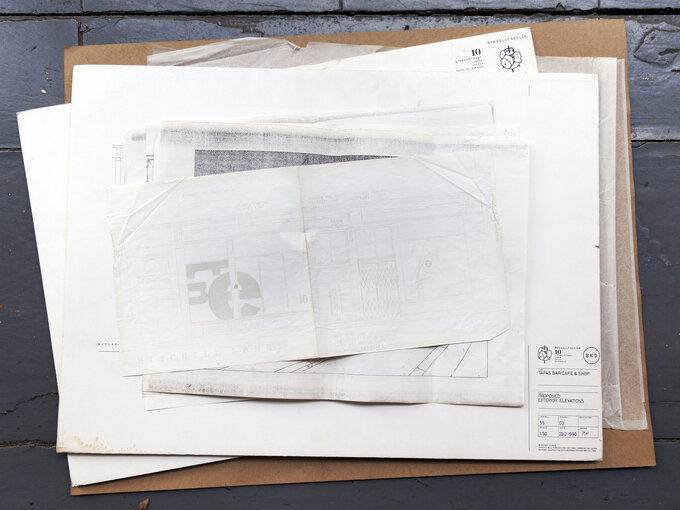

Elevations of Bar Ten and DLC on the junction of Mitchell Lane and Gordon Lane in Glasgow.

>

In my recollection, it went through a number of transitions that overlapped with the people who were running it at the time. I remember being in there from the very beginning. I would have known Sam Piacentini or certainly known of Sam from the City Café in Edinburgh – which was really the only cool place in Edinburgh.

Above. Sketches of Bar Ten window graphics.

Below. The interior of Bar Ten by Ben Kelly.

That was at a time when everybody in Edinburgh was wearing green wellies and rainbow knits, so it was quite extraordinary. Then Bar Ten appeared and I’d love to hear about how that relationship happened. Did he just call you up out of the blue or did you know him? How did that commission arrive?

I can tell you, it was quite an experience for me. I think the phone call came out of the blue in the first instance. The phone call from Sam came after (unbeknown to me) he had travelled from Edinburgh, where he lived, to Manchester and he went to the DRY 201 from the moment it opened in the morning, and he sat in that place until the moment it closed in the evening! He absorbed and observed the kind of cycle of it, and that experience convinced him that he should make the phone call. So I get the phone call which I thought, “Who or what is this person!” Because never having any previous experience, or even heard of Sam Piacentini at that time, it was quite a rollercoaster phone call! He didn’t talk as much as shouted on the phone! But I rolled with it, and found myself on an aeroplane going to Edinburgh where I was met by Mr Sam Piacentini in a very sharp suit, to be driven in his BMW from Edinburgh to Glasgow. We drove to Glasgow and it poured with rain that entire day. He dragged me around every kind of watering hole or fashion shop. He gave me the lay of the land and what was happening at that moment in time in Glasgow. And then of course we looked at the site, which at that point was just one single volume space, which we eventually split in two.

There we were, dripping like wet rats and back into his BMW and whizzed back to Edinburgh. He had previously told me that he would provide accommodation for me to stay over that night and we pulled up outside a tenement block, that had a bar at ground floor level, and we went into the bar and immediately consumed a very large whisky to recover from a day of being soaked with rain. And he looked at me and said “Oh, by the way, you do know that I’m gay don’t you!” I thought “Shit, no Sam I’ve got no bloody idea, I couldn’t care less but…” and then he said “and you’re staying at my place!” So we then go up many flights of stairs to his airy loft up there at the top. We had a pleasant evening, and dried out and chatted and drank some more. He gave me his bed, saying “Oh I’ve only got one bedroom in this little apartment,” and explained that he would sleep on the settee. Anyway I go to bed and after an hour or so I developed a really, really bad cough as a result of the drenching. The next thing I remember, he came bounding in with a giant spoonful of Nightnurse and shoved it down my throat! I have no memory from there on!

Who knows what happened!

I drew a blank there but anyway, that was that! And also, yes of course he took me to the City Café and I could sense, here was a man with some style and passion and as the days and weeks drew on, the thing developed. Then he introduced me to his business partner. He was 10 times weirder that Sam could ever be… if that is possible! He was running a pub in Leith, down by the dock, it got even more surreal! It turned out that he was a bit of a ne’er-do-well. His father had been a very successful architect and had been responsible for a lot of the concrete monstrosities in Glasgow in the ‘60s & ‘70s and made a serious amount of money, and his son was living off the proceeds, I think. And he was running this dodgy, ramshackle bar down in Leith that I think Merchant Seaman used to go to and he put on a light show. It was the most kind of amateurish, dodgy light show and girls dancing…

>

Of course yeh, Edinburgh was famous for that at the time. It had these Go-Go dancer bars that weren’t allowed in Glasgow. So when we were students we would obviously go through and check it out.

Faxed elevation of the Bar Ten and DLC window graphics.

He was eccentric in a completely different way to the way Sam was eccentric. There was a charm about him, and he was supposed to be the business partner and I think that he was partly funding the operation. I remember we went to a party in his eccentric father’s bloody castle somewhere up north in the wilds of Scotland, with all these mad people! It was like going into Monty Python. But we soldiered on and Sam was amazing – a dog with a bone – he wouldn’t let it go!

And then of course we met Derek and the DLC people.

Was that always the idea? That it would be a bar and hairdressers?

It was, although I think at the very beginning that wasn’t totally clear to me. I think he knew that he wanted to split it into two – whether he had DLC lined up from the outset or not, I’m not sure, or whether they came along slightly after we had started. I’m really not certain about that.

I had a guy working in my office at the time, a guy called Peter Mance, who got on really well with DLC and became friendly with them and he became the project architect. He had to come up and stay over and run the job and I thought “I’m not doing this, I don’t have the stamina for it!“

As it went on, I can remember right towards the end when there were deadlines (and I’m not sure what was driving the deadlines) and I think funding was becoming slightly problematic, but Sam was relentless with wanting the best of everything, of course. And there was some issue over some stainless steel stuff behind the bar. The press were starting to get involved, but I remember one point where Sam took me right to the edge – right to the limit, that I actually had my forearm against his throat, up against the wall of the interior saying “You bastard, this is enough, I can’t take it anymore!” There might have been a photographer lurking in the background, and I thought I’d better cool down here.

The crowning glory of it all – there was a big opening event for which he flew me, and about three people from my office, up for this event – very generous, and we were met up at the airport by a limo—a chauffeur driven limo—we swept into Glasgow and the driver sat in the front (he might even have had a peaked cap on) and we’re sat in the back and he was curious as to what was going on. I couldn’t do his accent, he was a real Glaswegian you know, asking what was the purpose of our visit and I sort of explained “Well, we’re here for the grand opening of a combination of a bar and a hair dressing salon,” and he went “Oh, a nip and a snip!” I thought this man is genius! He had it in a second and I thought that is just magical and it set it up just nicely for the evening.

He was a strong character Sam, and I remember especially in the early days he was just so rude to everybody that came into the bar. He would stand behind the bar and be really off-hand with people, and some people just went straight out again. And others realised that it was just his slightly tongue-in-cheek way of telling you that he liked you.

He described it a bit like he wanted the bar to be like a classic car where it was built to last and you could polish it up and it ran really nicely, and I thought that analogy was great. On jobs that we’ve done, I’d always try to build things to last and I know that it’s quite transient and change is inevitable, but if you build a bloody thing that’s difficult to knock down, there’s a chance it might last a little bit longer.

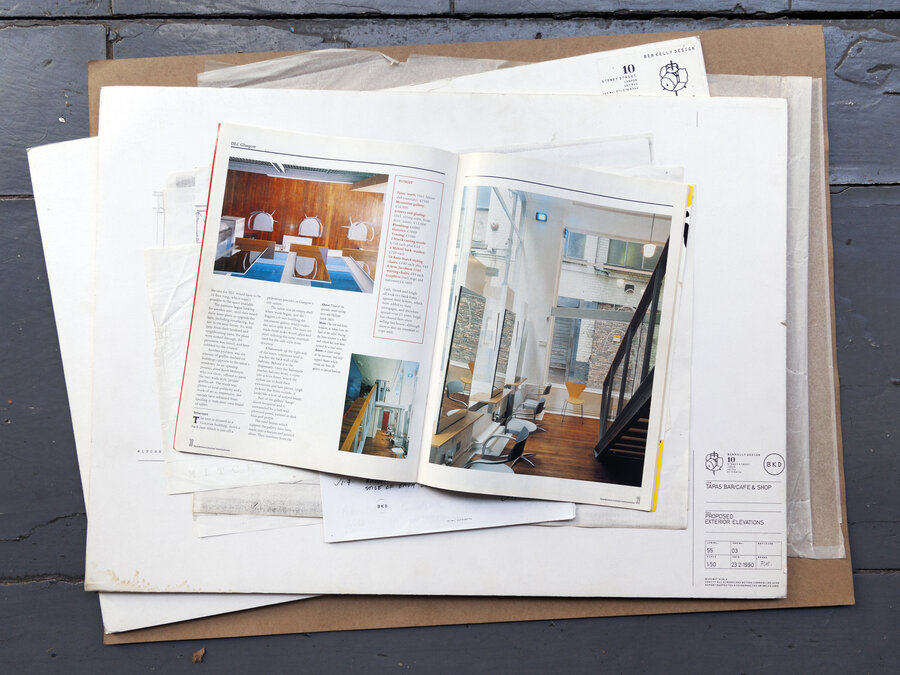

Article in Hairdressers Journal International showing the completed interiors of DLC.

>

I think for me, what you’ve just described is really interesting because I always felt that Bar Ten had something of a product about it. It was like a piece of product design and you know what it’s like when you do any interior or any piece of architecture it’s always a kind of prototype – you never get to do it again. The quality of the making in Bar Ten was phenomenal. The terrazzo, the granite top, the stainless steel elements – all of that stuff was so well made and thinking back, who actually made it?

Dry Bar, Manchester. By Ben Kelly.

The quality of the making in Bar Ten was phenomenal. The terrazzo, the granite top, the stainless steel elements – all of that stuff was so well made and thinking back, who actually made it?

Well it was a firm of local contractors, and for the life of me I can’t remember their name, and I can’t remember who found them or who procured them. And I think that they were pushed to the limit also, and I remember going to meetings at their place.

I’m just thinking back to our (Graven Images) first interiors. Our first bar in Glasgow was probably in ’93, we did a place called The Lounge, and we had a budget of 16 grand and it was thrown together with string and it was impossible to get any quality. I guess, back then it must have been similar in Manchester in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, that I guess there weren’t that many interior designers. The number of interior designers in Glasgow when we started our business was one or two – it was quite a different landscape.

Absolutely, and now they’re ten a penny. Millions, all being churned out of art schools.

Let’s talk a little bit more about Bar Ten. I wanted to ask you a bit about your early time – how you got to that. I don’t know to what extent this was conscious – but it had this feeling of being a cross between a Glasgow bar, a proper standing up bar, rather than a pub – and those archetypal European cafés.

You beat me to it! I remember when we did the Dry Bar in Manchester, and my clients Factory Records in their infinite wisdom or foolhardiness, sent me, a guy called Paul Mason who managed The Haçienda, and another guy Leroy Richardson who was going to manage Dry Bar. We were sent on a research trip to Los Angeles and New York.

What did you find in LA at that time that could have been of any benefit?

Well Frank Gehry had done a few restaurants and there was another very arty firm of architects doing a few bars, and then there’s plenty to look at in New York obviously. But in my mind, that trip was all about understanding service. Service in America is another story altogether. Whereas service in Manchester then was something else. We came back and I thought shit, I don’t want people thinking I’ve gone to America looking for ideas. My models, my inspiration, always came from Europe, both with the Dry Bar which I saw as a kind of – not a Parisian thing – but there was something European and continental about the way it sort of changed through the day.

I wanted it to be something that belonged and you felt comfortable there. Something that you could relate to and feel it was solid and it wasn’t about fashion and trends and all of that stuff. That it had integrity, and that came through the use of materials, through craftsmanship, through the way that all the component parts went together.

It’s a great example of that.

Sorry Ross I keep interrupting you, but I will say that my favourite bar in the whole wide world, has to be the Adolf Loos bar in Vienna, the American Bar, the Karntner bar, and that holds magic to me that little bar, and that’s what set me alight and was in the back of my mind all the time.

The thing that I thought was interesting about Bar Ten was how it evolved. Sam had his own way of presenting it. Then an interesting thing happened when Steven and Michael took it over and they definitely understood it and respected it, but they had fun with it at the same time. So they had these ridiculous camp exhibitions on and they messed with it a little bit. It was a brilliant party place and there were many lock-ins and very late nights.

I suppose Derek Farquharson, in particular – the “D” in DLC – was probably the biggest protagonist for Bar Ten and of your work through the more recent years until he sadly died just earlier in the year.

What’s become of that part of it just now?

I know that Derek, and his partner Rod, had some of your drawings in a file somewhere at home.

Anyway I was going to ask about the bit before. So Bar Ten was what, ’91, ’92, something like that? I saw that you grew up in Appletreewick, and I had a little Google Streetview walk down the road and I wondered if you’d ever had a few late nights in the New Inn. I thought, that looks like my kind of pub!

Oh dear, well that pub, for a good few years was run by the most bizarre man, who was well ahead of his time you could say – he banned smoking in his pub. This was decades before smoking became outlawed. He had a massive bucket of water behind the bar, if anyone lit up and he told them to put it out and if they didn’t, he’d just empty the bucket of water all over them!

>

So, what did you do – where did you study?

Seditionaries shop front by Ben Kelly for Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood.

I went to art school in 1966, in Lancaster, and they did a weird interior design course. It wasn’t nationally recognised and I probably didn’t have enough qualifications or ‘O Levels’ or whatever you needed to get on a proper course, so I did a kind of foundation there and then I did this interior design course. Then eventually I went to the Royal College in London and did three years there as a postgraduate.

Then did you go back to Manchester after that, or did you stay in London?

I never ever lived in Manchester, people do think that. From Lancaster I went straight to London and before Lancaster I was at school, living in Appletreewick, North Yorkshire in the Yorkshire Dales – 27 houses, 2 pubs and a church.

And how did you survive in those early, difficult days?

In the beginning for me, my girlfriend did Fashion at the RCA and we met there and she started selling clothes to various people who opened shops and things, and then people said “Oh, would you design my shop?” and then one of these people got quite successful and became a successful PR person and I designed big offices for them and it just grew. And then also I had met Malcolm (McLaren) and Vivienne (Westwood), so I was involved with them so I did rehearsal rooms for the sex pistols, an apartment for Steve Jones the guitarist, and I did some offices for Malcolm’s company Glitterbest. Then Malcolm and Vivienne kept changing the shop and it became Seditionaries, and Malcolm asked me to help out with the shopfront of Seditionaries. I met Peter Saville eventually and we did some record sleeves together and then lo and behold The Haçienda happened and then Dry and then the (Factory) HQ building. We did a headquarters building for another independent record company, 4AD, in Wandsworth. So as I describe it, I was working for friends of weirdos and wackos – all kinds of creative people who were just trying to do something interesting which is what happened then, decades before Hoxton and the so called Hipsters happened.

I love the fact that it doesn’t sound like you had a business plan and I can completely relate to that.

No it was totally organic. But what did happen, because I was sort of the early wave of it, in the first wave possibly in the mid ‘70s. And then in the ‘80s, design just went mental and many design practices were going up – I described it like they were appearing through cracks in the pavement. Design was like a disease – you caught it over night! The companies were getting backers, and banks were putting money in, but what was happening was that they were taking long leases and big premises and they got themselves into trouble. And as quickly as a lot of them appeared, they disappeared. People like myself, who were kind of tucked away in a corner, ploughed on and came out at the other end of it. I think it’s a bit like a filtering system – the crap and the shit that happened, disappeared and people that were trying to hang onto a bit of integrity, came out at the other end. I closed my office about three and a half years ago. I’d been in Borough Market for over 30 years. I now work on my own but I don’t pitch for anything and I don’t chase anything. I am lucky – clients make contact and ask if I would like to do a project. I can decide to say yes or no.

Because of The Haçienda, in the early days I described it as a ‘monkey on my back’, it just wouldn’t go away! It’s like that’s all I ever did, which it bloody well isn’t. But time has kind of washed that away, and now it’s turned around and it’s led onto all sorts of things.

The Haçienda, Manchester. By Ben Kelly.

>

I’m sure that in retrospect you can’t see it as having been a bad thing. I liked that online The Haçienda and Studio 54 are kind of pushed together as the two iconic clubs of all time and I think that’s wonderful. I did manage to make it to Studio 54, in the very twilight years of it. It would have been 1983 when I was in New York. At least I ticked that box on my bucket list.

'Columns' by Ben Kelly.

Well I actually met, only about a year and a half ago, I met Steve Rubell. Do you get to London much?

It depends, It depends what we’re doing, I haven’t been down in the last couple of months.

Do you know the place called 180 The Strand? It’s a huge brutalist office building. Well I’m quite involved with that building and its owner, and I’ve put on two installations there – one big one which was called ‘Ruin’ which was a ruined night club and that has led on to all sorts of things. And I don’t know if you know about Virgil Abloh, he has a fashion label called ‘Off-White’ and he’s the menswear designer at Louis Vuitton, and he’s a guy from Chicago. He copied the stripes that I put on columns of The Haçienda on his Off-White garments. He’s now the most sought-after man in the fashion world, on the planet, bar none at the moment. But I got angry with him to start with, “He’s ripping me off”… but he eventually found me and asked me to do something – and we’ve collaborated on many different projects. And that platform now has led me to all sorts of other territories.

I like that broadening of your practice. I think that when we were educated the expectation was that if you study interior design then that’s what you were going to do. If you study Graphics then you would be stuck in that narrow zone and actually there’s no reason why it should be like that. If you’re a trained designer then you’re a trained designer – the process is the same.

I’ve encouraged collaboration all the time, always. And we’ve strayed into all sorts of territories. And now because of the kind of position that I’m in, I’m more interested in doing installations. I dipped my toe in the art world, and I’m interested in commenting on design and the kind of relationship between art and design and what’s happening in the world. At 180 The Strand I’ve been allowed to do certain things. And I want to do things that resonate with people, that they can see where all the bits are glued together. But I’m interested in the idea of ruins because society is becoming a great big ruin! If I can make comment through design, with these kind of installations – I want to make people think and look at things and think about things, and re-assess and analyse ‘what’ and ‘why’ and ‘where’.

I really liked on your website a piece that’s just called ‘Column’, I’d never seen that before and I really liked it. It made me think of one of those geological cores where they kind of drill down and pull out a piece of rock.

Yeh that’s what it’s about really, those strata.

I loved that, I thought that was great. In a funny way, we are talking about transience again, and that idea that sometimes you do something and it might be important and it might be powerful and it might be emotionally connected, but it can’t last forever and you probably just have to go, ’take a picture and move on’.

- 10. Simon Murphy

- Kate Trouw. Pettycur

- Heavenly Bodies. Hanon x Forward

- Take a Picture and Move On

- Like Tears in the Rain

- Sleeve Notes. The Twilight Sad

- Soul Food Sisters

- Poppy Nash