02 —

It Can't Happen Here

Writer and broadcaster Stuart Cosgrove reflects on renewed interest in the documentary photography of the US-Japanese Internment Camps.

Donald Trump's presidency has unleashed prejudices that few thought possible. The days of 'hope over fear' have crashed against the rocks of a new and alarming reality. The alternative-right have cheered Trump into high office and he has rewarded them with positions in high-power and attention seeking policies.

The Hirano family, left to right, George, Hisa,

and Yasbei. Colorado River Relocation Center,

Poston, Arizona, 1942

Photograph, Unknown

US. National Archives

Whilst protests have followed Trump's every move, a war of ideas has broken out the likes of which we have not seen since the 1930s. You can feel the anger in tribal spaces online, and in the furious real-world, where demonstrations have engulfed Trump's flagship hotel and gridlocked cities across America.

One of the less visible reactions to Trump's presidency has been renewed interest in the critical art of repressive America: books, art works and photography that in the past challenged America's self-serving narrative of unbroken democracy. One of the most visible manifestations of this trend has been the re-publication and online sales-success of Sinclair Lewis's classic anti-fascist novel 'It Can't Happen Here.' (1935) The title has become a by-word for disbelief about America's susceptibility to fascism and the gruesome extremes of populism.

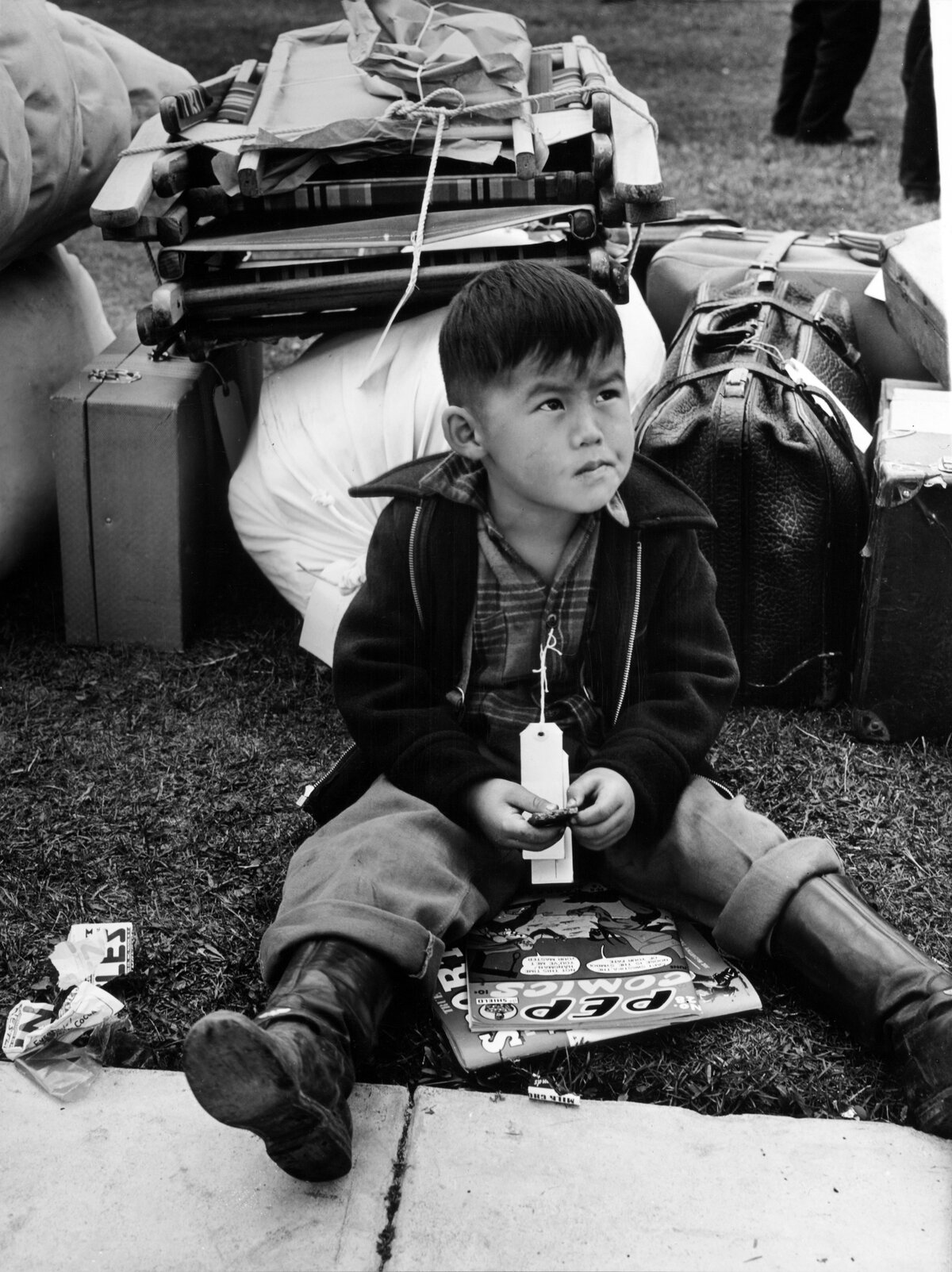

Tagged for evacuation, Salinas, California, May 1942 Photograph, Russell Lee US Farm Security Administration (*FSA) 1942

Sinclair's satirical book tells the story of a far-right wing demagogue, Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, and his rise to power in America.

Richard Kobayashi, farmer with cabbages, Manzanar Relocation Center, California

Photograph, Ansel Adams Library of Congress

Written in the febrile era of the great depression, when capitalism teetered on the brink of total collapse, it was a mid-century modern classic, whose time has unexpectedly come again. So to the cruelly satirical novel, 'A Cool Million: The Dismantling of Lemeul Pitkin' (1934) by Nathaniel West, a brilliant savaging of the myths of populism.

Another area of renewed fascination is the social photography of Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, who were employed by the Federal Government to record society in the depression years – the dust-bowl poverty, inner city deprivation and the grand job-creation schemes funded by President Roosevelt to rebuild the national infrastructure. One strand of their work has been recently reactivated – the photographs that recorded the internment of Japanese Americans, in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbour. The comparisons between the Japanese then and the treatment of Muslim Americans and Mexicans now is chillingly relevant.

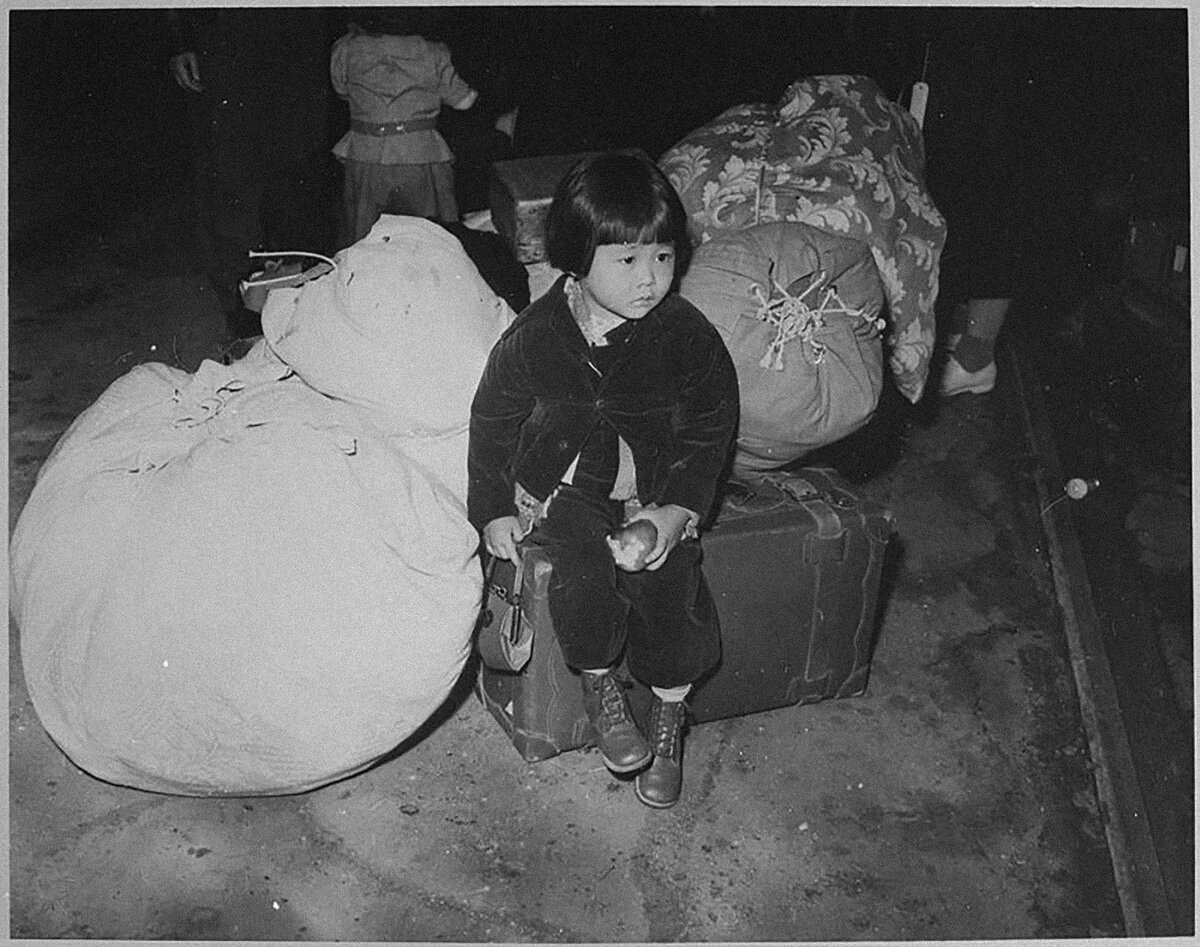

In February 1942, two months after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt as commander-in-chief, issued Executive Order 9066, relocating all persons of Japanese ancestry, both citizens and aliens, inland and away from the Pacific coast's military zone.

Japanese men harvest spinach at the Tule Lake Relocation Center, September 8, 1942 Photograph, Francis Stewart War Relocation Authority Office Photographer US National Archives

A Japanese child evacuee with family belongings en route to an internment assembly center, Spring 1942 Photograph, unknown

The objective was to prevent espionage, sabotage and more generously to provide a place of protection for Japanese citizens who had come under fierce racial attack. The Japanese Relocation centres were situated many miles from the military installations along the coast, often in remote and desolate locales. Sites included Tule Lake, California; Minidoka, Idaho; Manzanar, California; Topaz, Utah; Jerome, Arkansas; Heart Mountain, Wyoming; Poston, Arizona; Granada, Colorado; and Rohwer, Arkansas. Around 117,000 people of Japanese descent were relocated to the internment camps, the vast majority of who were already American citizens.

Families were bundled from their homes, and taken inland by coach and truck to camp sites where in many cases they were expected to build their new homes, makeshift huts that resembled the wooden huts of German Prisoner of War camps.

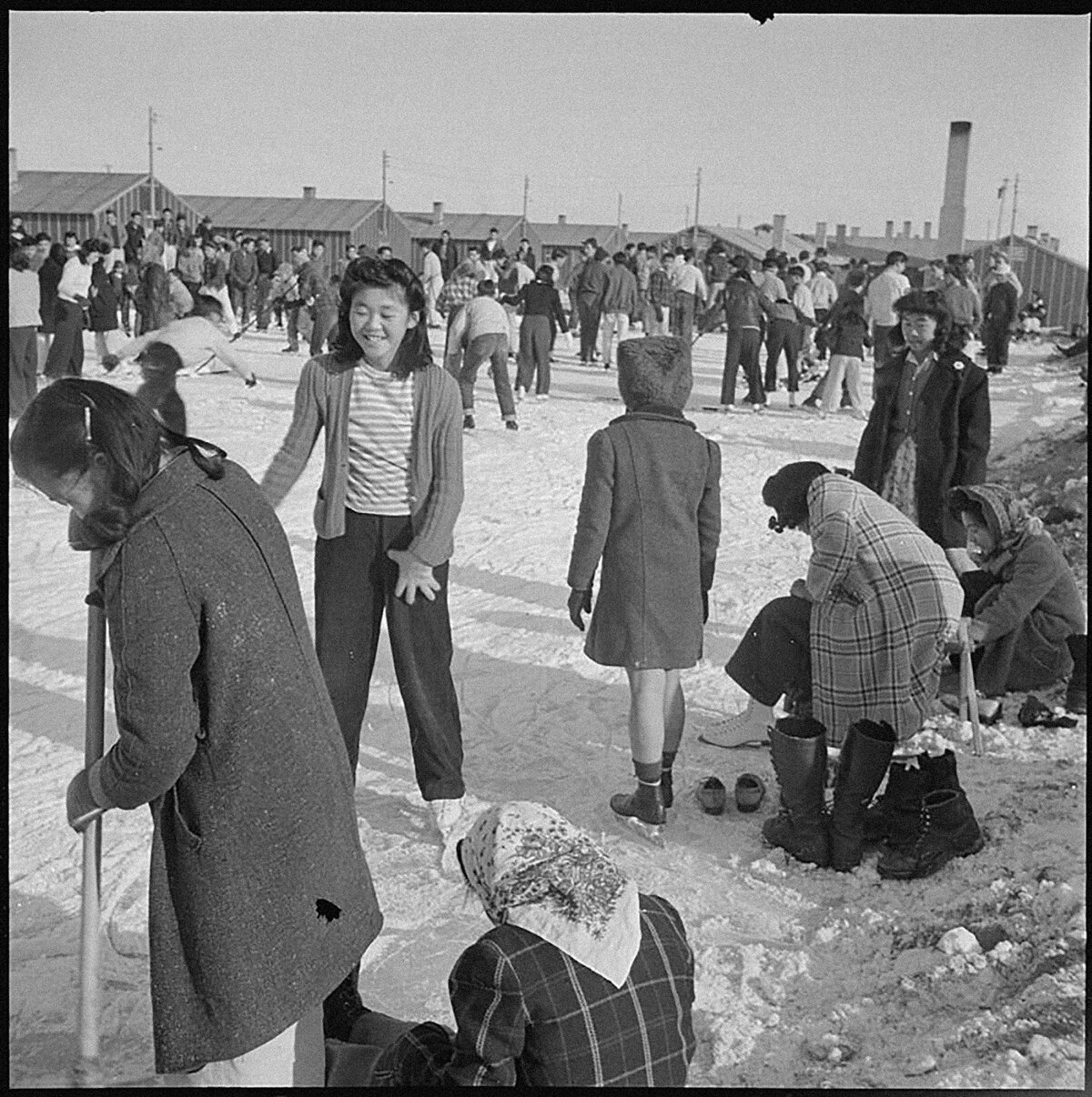

The interred families, farmed the land to provide food, in a 'forced labour' policy that stopped far short of the brutal hard labour of Russian gulags, and at least in their willingness to tolerate community building, were unlike the Stalag camps of central Europe. Families stayed together, and their internment was an act of war rather than peace, in that respect they bore greater similarity to the UK's internment of 4,000 Italian families in wartime Britain. Many Italian-Scots were shipped to internment on the Isle of Man, and others died when the transportation vessel, the Arandora Star which was sunk by U-Boats in 1940. In an act of war-time pragmatism or callous racism, Winston Churchill had given the instruction to "collar the lot."

Japanese girls doing keep-fit calisthenics at Manazar Camp Photograph, Unknown

A community of sorts emerged out of the Japanese internment camps. Remarkably two of America's most gifted documentary photographers – Lange and Adams were granted permission to photograph the camps.

Members of the Mochida family awaiting an evacuation bus. Identification tags were used to keep the family intact during all phases of evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses on a two-acre site in Eden Township. He raised snapdragons and sweet peas.

Photograph, Dorothea Lange

US National Archives

What they found was not always crude repression but images of a society forced to survive in internal exile, required to build a new life away from their own homes. Adams took up brief residence in one of the biggest internment camps the Manzanar Relocation Center, California which as more and more Japanese families were arrested, grew to be the size of a small makeshift town. For a period in 1942 had the biggest population of Japanese in the USA and somehow they preserved a sense of society under duress. The photographs are a unique glimpse into a society under strain where racial profiling, enforced segregation and state planned internment became the norm in a society whose constitution – and democratic narrative – was supposed to defend its citizens.

In 1944 a Japanese born US citizen Fred Korematsu challenged the constitutionality of the internment camps in the Supreme Court but lost his case and the camps did not close down until after the war was over. In 1988 President George W. Bush apologised to the surviving families and agreed to pay compensation for their forced relocation.

Heart Mountain Relocation Center, 10 January 1943 Photograph, Tom Parker US National Archives

These images raise the nagging prospect that internment on grounds of race and ethnicity is a recent memory, proof that 'It Can Happen Here'.

Grandfather and grandson at Manzanar Relocation Center, California July 2, 1942

Photograph, Dorothea Lang

US National Archives